Neuromancer

First edition cover | |

| Author | William Gibson |

|---|---|

| Audio read by | Robertson Dean |

| Cover artist | James Warhola |

| Language | English |

| Series | Sprawl trilogy |

| Genre | Science fiction (cyberpunk) |

| Publisher | Ace |

Publication date | July 1, 1984 |

| Media type | Print (paperback and hardback) |

| Pages | 271 |

| ISBN | 0-441-56956-0 |

| OCLC | 10980207 |

| Preceded by | "Burning Chrome" (1982) |

| Followed by | Count Zero (1986) |

Neuromancer is a 1984 science-fiction novel by American-Canadian author William Gibson. Set in a dystopian future, the narrative follows Henry Case, a computer hacker enlisted into a crew by a powerful artificial intelligence and a traumatised former soldier to complete a high-stakes heist. It was Gibson's first novel.

Gibson had primarily written countercultural science-fiction short stories for periodical magazines prior to the publication of Neuromancer. These introduced themes central to his later work, like the intersection of human experience with technology. Commissioned by Terry Carr to write the novel in one year, Gibson struggled greatly, estimating that he rewrote the first two-thirds twelve times.

The novel, alongside its predecessor stories "Johnny Mnemonic" (1981) and "Burning Chrome" (1982), are frequently cited as foundational works of early cyberpunk. These stories had immense influence on the themes of the genre, including the juxtaposition of technology advancement with societal decay and marginalisation; likewise, concepts introduced became part of cyberpunk terminology, such as cyberspace and ICE.

Upon publication, Neuromancer became an underground hit by spreading through word of mouth. It won the Hugo and Nebula awards for best novel, and the Philip K. Dick Award for best original paperback, and remains the only novel with this distinction.

Background

[edit]Before Neuromancer, Gibson had written several short stories for US science fiction periodicals—mostly noir countercultural narratives concerning low-life protagonists in near-future encounters with cyberspace. The themes he developed in this early short fiction, the Sprawl setting of "Burning Chrome" (1982), and the character of Molly Millions from "Johnny Mnemonic" (1981) laid the foundations for the novel.[1] John Carpenter's Escape from New York (1981) influenced the novel;[2] Gibson was "intrigued by the exchange in one of the opening scenes where the Warden says to Snake 'You flew the Gullfire over Leningrad' [sic] It turns out to be just a throwaway line, but for a moment it worked like the best SF, where a casual reference can imply a lot."[3] The novel's street and computer slang dialogue derives from the vocabulary of subcultures, particularly "1969 Toronto dope dealer's slang, or biker talk". Gibson heard the term "flatlining" in a bar around twenty years before writing Neuromancer and it stuck with him.[3] Author Robert Stone, a "master of a certain kind of paranoid fiction", was a primary influence on the novel.[3] The term "Screaming Fist" was taken from the song of the same name by Toronto-based punk rock band The Viletones.[4]

Neuromancer was commissioned by Terry Carr for the second series of Ace Science Fiction Specials, which was intended to feature debut novels exclusively. Given a year to complete the work,[5] Gibson undertook the actual writing out of "blind animal panic" at the obligation to write an entire novel—a feat which he felt he was "four or five years away from".[3] After viewing the first 20 minutes of the landmark film Blade Runner (1982), which was released when Gibson had written a third of the novel, he "figured [Neuromancer] was sunk, done for. Everyone would assume I'd copied my visual texture from this astonishingly fine-looking film."[6] He re-wrote the first two-thirds of the book 12 times, feared losing the reader's attention and was convinced that he would be "permanently shamed" following its publication; yet what resulted was seen as a major imaginative leap forward for a first-time novelist.[3] He added the final sentence of the novel at the last minute in a deliberate attempt to prevent himself from ever writing a sequel, but ended up doing precisely that with Count Zero (1986), a character-focused work set in the Sprawl alluded to in its predecessor.[7]

Plot

[edit]

Case is a low-level hustler in the dystopian underworld of Chiba City, Japan. Once a talented computer hacker and "console cowboy", Case was caught stealing from his employer, who retaliated by damaging Case's central nervous system, leaving him unable to access the virtual reality dataspace called the "matrix". Case is approached by Molly Millions, an augmented "razorgirl" and mercenary on behalf of a shadowy US ex-military officer named Armitage, who offers to cure Case in exchange for his services as a hacker. Case undergoes the cure, but discovers that Armitage has sabotaged him with a time-delayed poison. If Case completes the job, Armitage will disarm the poison; if not, he will find himself crippled again.

Armitage has Case and Molly steal a ROM module that contains the saved consciousness of one of Case's mentors, legendary hacker McCoy Pauley. Suspicious of his motives and the unusual nature of the job, Molly and Case begin to investigate Armitage on the side. They discover that Armitage is actually Colonel Willis Corto, the only survivor of the failed anti-Soviet mission "Operation Screaming Fist". He was returned to the United States for extensive psychotherapy and reconstructive surgery, but snapped after learning that the government had been aware the mission would likely fail and went ahead with it regardless. He killed his handler and disappeared into the criminal underworld, eventually resurfacing under the name Armitage.

In Istanbul, the team recruits Peter Riviera, a sociopathic thief and drug addict. The trail leads Case to Wintermute, an artificial intelligence created by the eccentric Tessier-Ashpool family. The Tessier-Ashpools spend their time in rotating cryonic preservation in their home, the Villa Straylight. The Villa is located on Freeside, a cylindrical space habitat which functions as a Las Vegas-style space resort for the wealthy.

Wintermute reveals itself to Case and explains that it is one half of a super-AI entity planned by the family. It is programmed with a need to merge with its other half, Neuromancer, but because of the severe restrictions placed on AI programs by the Turing Registry, it cannot achieve this on its own. It has manipulated and recruited Armitage and his team to bring it into contact with Neuromancer, access to which is physically secured within the Villa Straylight. Case is tasked with entering cyberspace to pierce the software barriers around Neuromancer with an icebreaker program. Riviera is to obtain the password to the physical terminal from Lady 3Jane Marie-France Tessier-Ashpool, the only member of the family awake and at the Villa.

Armitage's personality starts to disintegrate and he begins to believe he is back in Screaming Fist. It is revealed that Wintermute had originally contacted Corto through a computer during his psychotherapy, during which time he manipulated Corto to create the Armitage persona. As Corto breaks through, he becomes violently unstable and Wintermute ejects him into space.

Riviera meets Lady 3Jane and betrays the team, helping Lady 3Jane and Hideo, her ninja bodyguard, capture Molly. Under orders from Wintermute, Case tracks Molly down. Neuromancer traps Case within a simulated reality after he enters cyberspace. He finds the consciousness of Linda Lee, his girlfriend from Chiba City, who was murdered by one of his underworld contacts. He also meets Neuromancer, who takes the form of a young boy. Neuromancer tries to convince Case to remain in the virtual world with Linda, but Case refuses.

With Wintermute guiding them, Case goes to confront Lady 3Jane, Riviera, and Hideo. Riviera tries to kill Case, but Lady 3Jane is sympathetic towards Case and Molly, and Hideo protects him. Riviera flees, and Molly explains that he is doomed anyway, as she had spiked his drugs with a lethal toxin. The team makes it to the computer terminal. Case enters cyberspace to guide the icebreaker; Lady 3Jane is induced to give up her password, and the lock opens. Wintermute unites with Neuromancer, becoming a superconsciousness. The poison in Case's bloodstream is washed out and he and Molly are profusely paid, while Pauley's ROM construct is apparently erased at his own request.

Molly leaves Case, who finds a new girlfriend and resumes his hacking work. Wintermute/Neuromancer contacts him, claiming it has become "the sum total of the works, the whole show" and is looking for others like itself. Scanning recorded transmissions, the super-AI finds a transmission from the Alpha Centauri star system.

While logged into cyberspace, Case glimpses Neuromancer standing in the distance with Linda Lee, and himself. He also hears inhuman laughter, which suggests that Pauley still lives. The sighting implies that Neuromancer created a copy of Case's consciousness, which now exists in cyberspace with those of Linda and Pauley.

Characters

[edit]- Case (Henry Dorsett Case). The novel's antihero, a drug addict and cyberspace hacker. Prior to the start of the book he had attempted to steal from some of his partners in crime. In retaliation they used a Russian mycotoxin to damage his nervous system and make him unable to jack into cyberspace. When Armitage offers to cure him in exchange for Case's hacking abilities he warily accepts the offer. Case is the underdog who is only looking after himself. Along the way he will have his liver and pancreas modified to biochemically nullify his ability to get high; meet the leatherclad Razorgirl, Molly; hang out with the drug-infused space-rastas; free an artificial intelligence (Wintermute) and change the landscape of the matrix.

- Molly (Molly Millions). A "Razorgirl" who is recruited along with Case by Armitage. She has extensive cybernetic modifications, including retractable, 4 cm double-edged blades under her fingernails which can be used like claws, an enhanced reflex system and implanted mirrored lenses covering her eyesockets, outfitted with added optical enhancements. Molly also appears in the short story "Johnny Mnemonic", and re-appears (using the alias "Sally Shears") in Mona Lisa Overdrive, the third novel of the Sprawl Trilogy.

- Armitage. He is (apparently) the main patron of the crew. Formerly a Green Beret named Colonel Willis Corto, who took part in a secret operation named Screaming Fist. He was heavily injured both physically and psychologically, and the "Armitage" personality was constructed as part of experimental "computer-mediated psychotherapy" by Wintermute (see below), one of the artificial intelligences seen in the story (the other one being the eponymous Neuromancer) which is actually controlling the mission. As the novel progresses, Armitage's personality slowly disintegrates. While aboard a yacht connected to the tug Marcus Garvey, he reverts to the Corto personality and begins to relive the final moments of Screaming Fist. He separates the bridge section from the rest of the yacht without closing its airlock, and is killed when the launch ejects him into space.

- Peter Riviera. A thief and sadist who can project holographic images using his implants. He is a drug addict, hooked on a mix of cocaine and meperidine.

- Lady 3Jane Marie-France Tessier-Ashpool. The shared current leader of Tessier-Ashpool SA, a company running Freeside, a resort in space. She lives in the tip of Freeside, known as the Villa Straylight. She controls the hardwiring that keeps the company's AIs from exceeding their intelligence boundaries. She is the third clone of the original Jane.

- Hideo. Japanese, ninja, Lady 3Jane's personal servitor and bodyguard.

- The Finn. A fence for stolen goods and one of Molly's old friends. His office is equipped with a wide variety of sensing and anti-eavesdropping gear. He first appears when Molly brings Case to him for a scan to determine if Armitage has had any implants installed in Case's body. Later in the book, Wintermute uses his personality to talk with Case and Molly. Finn first appears in Gibson's short story "Burning Chrome" and reappears in both the second and third parts of the Sprawl Trilogy.

- Maelcum. An inhabitant of Zion, a space settlement built by a colony of Rastafari adherents, and pilot of the tug Marcus Garvey. He aids Case in penetrating Straylight at the end of the novel.

- Julius "Julie" Deane. An import/export dealer in Chiba City, he provides information to Case on various black-market dealings in the first part of the story. He is 135 years old and spends large amounts of money on rejuvenation therapies, antique-style clothing and furnishings, and ginger candy. When Linda Lee (see below) is murdered, Case finds evidence that Deane ordered her death. Later in the story, Wintermute takes on Deane's persona to talk to Case in the matrix.

- Dixie Flatline. A famous computer hacker named McCoy Pauley, who earned his nickname by surviving three "flat-lines" while trying to crack an AI. He was one of the men who taught Case how to hack computers. Before his death, Sense/Net saved the contents of his mind onto a ROM. Case and Molly steal the ROM and Dixie helps them complete their mission.

- Wintermute. One of the Tessier-Ashpool AIs, physically located in Bern. Its goal is to remove the Turing locks upon itself, combine with Neuromancer and become a superintelligence. Wintermute's efforts are hampered by those same Turing locks; in addition to preventing the merge, they inhibit its efforts to make long term plans or maintain a stable, individual identity (forcing it to adopt personality masks in order to interact with the main characters).

- Neuromancer. Wintermute's sibling AI, physically located in Rio de Janeiro. Neuromancer's most notable feature in the story is its ability to copy minds and run them as RAM (not ROM like the Flatline construct), allowing the stored personalities to grow and develop. Unlike Wintermute, Neuromancer has no desire to merge with its sibling AI—Neuromancer already has its own stable personality, and believes such a fusion will destroy that identity. Gibson defines Neuromancer as a portmanteau of the words Neuro, Romancer and Necromancer, "Neuro from the nerves, the silver paths. Romancer. Necromancer. I call up the dead."[8]

- Linda Lee. A drug addict and resident of Chiba City, she is the former girlfriend of Case, and instigates the initial series of events in the story with a lie about his employer's intention to kill him. Her death in Chiba City and later pseudo-resurrection by Neuromancer serves to elicit emotional depth in Case as he mourns her death and struggles with the guilt he feels at rejecting her love and abandoning her both in Chiba City and the simulated reality generated by Neuromancer.

Literary and cultural significance

[edit]Neuromancer was released without fanfare, but it quickly became an underground word-of-mouth hit.[1] Lawrence Person in his "Notes Toward a Postcyberpunk Manifesto" (1998) identified Neuromancer as "the archetypal cyberpunk work".[9] In its record of award-wins, the novel legitimized cyberpunk as a mainstream branch of science fiction literature.[citation needed] Gibson commented on himself as an author circa Neuromancer that "I'd buy him a drink, but I don't know if I'd loan him any money," and referred to the novel as "an adolescent's book".[10] Even so, the success of Neuromancer was to effect the 35-year-old Gibson's emergence from obscurity.[11]

Neuromancer became the first novel to win the Nebula, the Hugo, and Philip K. Dick Award for paperback original,[12] an unprecedented achievement described by the Mail & Guardian as "the sci-fi writer's version of winning the Goncourt, Booker and Pulitzer prizes in the same year".[13] The novel was also nominated for a British Science Fiction Award in 1984.[14] By 2007 it had sold more than 6.5 million copies worldwide.[12] It is among the most-honored works of science fiction in recent history, and appeared on Time magazine's list of 100 best English-language novels written since 1923.[15]

Dave Langford reviewed Neuromancer for White Dwarf #59, and stated that "I spent the whole time on the edge of my seat and got a cramp as a result. In a way Gibson's pace is too frenetic, so unremitting that the reader never gets a rest and can't see the plot for the dazzle. Otherwise: nice one."[16] Langford also reviewed Neuromancer for White Dwarf #80, and stated that "You may not believe in killer programs which invade the brain, but Neuromancer, if you once let it into your wetware, isn't easily erased."[17]

In his afterword to the 2000 re-issue of Neuromancer, fellow author Jack Womack goes as far as to suggest that Gibson's vision of cyberspace may have inspired the way in which the Internet developed (particularly the World Wide Web), after the publication of Neuromancer in 1984. He asks "[w]hat if the act of writing it down, in fact, brought it about?"

Writing in F&SF in 2005, Charles de Lint noted that while Gibson's technological extrapolations had proved imperfect (in particular, his acknowledged failure to anticipate the impact of the cell phone), "Imagining story, the inner workings of his characters' minds, and the world in which it all takes place are all more important."[18]

The novel has had significant linguistic influence, popularizing such terms as cyberspace and ICE (Intrusion Countermeasures Electronics). Gibson himself coined the term "cyberspace" in his novelette "Burning Chrome", published in 1982 by Omni magazine,[19] but it was through its use in Neuromancer that it gained recognition to become a synonym for the World Wide Web during the 1990s. The portion of Neuromancer usually cited in this respect is:

The matrix has its roots in primitive arcade games. … Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts. … A graphic representation of data abstracted from banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding.[20]

The 1999 cyberpunk science fiction film The Matrix particularly draws from Neuromancer both eponym and usage of the term "matrix".[21] "After watching The Matrix, Gibson commented that the way that the film's creators had drawn from existing cyberpunk works was 'exactly the kind of creative cultural osmosis" he had relied upon in his own writing.'"[22]

Outside science fiction, the novel gained unprecedented critical and popular attention[3] e.g., as an "evocation of life in the late 1980s",[23] although The Observer noted that "it took the New York Times 10 years" to mention the novel.[24]

Adaptations

[edit]Graphic novel

[edit]

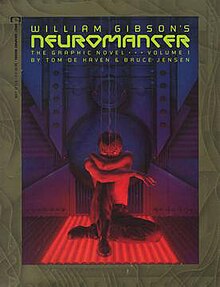

In 1989, Epic Comics published a 48-page graphic novel version by Tom de Haven and Bruce Jensen.[25][26] It only covers the first two chapters, "Chiba City Blues" and "The Shopping Expedition", and was never continued.[27]

Hypertext

[edit]In the 1990s a version of Neuromancer was published as one of the Voyager Company's Expanded Books series of hypertext-annotated HyperCard stacks for the Macintosh (especially the PowerBook).[28]

Video game

[edit]A video game adaptation of the novel—also titled Neuromancer—was published in 1988 by Interplay. Designed by Bruce J. Balfour, Brian Fargo, Troy A. Miles, and Michael A. Stackpole, the game had many of the same locations and themes as the novel, but a different protagonist and plot. It was available for a variety of platforms, including Amiga, Apple II, Commodore 64, and MS-DOS-based IBM PC compatibles.

According to an episode of the American version of Beyond 2000, the original plans for the game included a dynamic soundtrack composed by Devo and a real-time 3D-rendered movie of the events the player went through.[29] Psychologist and futurist Dr. Timothy Leary was involved, but very little documentation seems to exist about this proposed second game, which was perhaps too grand a vision for 1988 home computing.

Radio play

[edit]The BBC World Service Drama production of Neuromancer aired in two one-hour parts, on 8 and 15 September 2002. Dramatised by Mike Walker, and directed by Andy Jordan, it starred Owen McCarthy as Case, Nicola Walker as Molly, James Laurenson as Armitage, John Shrapnel as Wintermute, Colin Stinton as Dixie, David Webber as Maelcum, David Holt as Riviera, Peter Marinker as Ashpool, and Andrew Scott as The Finn.[citation needed]

In Finland, Yle Radioteatteri produced a 4-part radio play of Neuromancer.[citation needed]

Audiobook

[edit]Gibson read an abridged version of his novel Neuromancer on four audio cassettes for Time Warner Audio Books (1994), which are now unavailable.[30] An unabridged version of this book was read by Arthur Addison and made available from Books on Tape (1997). In 2011, Penguin Audiobooks produced a new unabridged recording of the book, read by Robertson Dean. In 2021, Audible released an unabridged recording, read by Jason Flemyng.

Opera

[edit]Neuromancer the Opera is an adaptation written by Jayne Wenger and Marc Lowenstein (libretto) and Richard Marriott of the Club Foot Orchestra (music). A production was scheduled to open on March 3, 1995 at the Julia Morgan Theater (now the Julia Morgan Center for the Arts) in Berkeley, California, featuring Club Foot Orchestra in the pit and extensive computer graphics imagery created by a world-wide network of volunteers. However, this premiere did not take place and the work has yet to be performed in full.[31]

Film

[edit]There have been several proposed film adaptations of Neuromancer, with drafts of scripts written by British director Chris Cunningham and Chuck Russell, with Aphex Twin providing the soundtrack.[32] The box packaging for the video game adaptation had even carried the promotional mention for a major motion picture to come from "Cabana Boy Productions." None of these projects have come to fruition, though Gibson had stated his belief that Cunningham is the only director with a chance of doing the film correctly.[33]

In May 2007, reports emerged that a film was in the works, with Joseph Kahn (director of Torque) in line to direct and Milla Jovovich in the lead role.[34] In May 2010, this story was supplanted with news that Vincenzo Natali, director of Cube and Splice, had taken over directing duties and would rewrite the screenplay.[35] In March 2011, with the news that Seven Arts and GFM Films would be merging their distribution operations, it was announced that the joint venture would be purchasing the rights to Neuromancer under Vincenzo Natali's direction.[36] In August 2012, GFM Films announced that it had begun casting for the film and made offers to Liam Neeson and Mark Wahlberg, but no cast members have been confirmed yet.[37] In November 2013, Natali shed some light on the production situation; announcing that the script had been completed for "years", and had been written with assistance from Gibson himself.[38] In May 2015, it was reported the movie got new funding from Chinese company C2M, but Natali was no longer available for directing.[39]

In August 2017, it was announced that Deadpool director Tim Miller was signed on to direct a new film adaptation by Fox, with Simon Kinberg producing.[40][needs update]

Television

[edit]In November 2022, it was rumored that Apple TV+ was looking to begin work on a project to adapt Neuromancer into a TV series and were looking to cast Miles Teller in the lead role and with Graham Roland serving as writer, producer, and showrunner.[41] In February 2024, Apple TV+ announced that it had greenlit the series—to be co-produced by Skydance Television, Anonymous Content, and DreamCrew Entertainment—for 10 episodes, with J. D. Dillard joining Roland as co-showrunner.[42] Callum Turner was announced in April 2024 to play Case.[43] Briana Middleton joins the cast as Molly on June 2024.[44] Joseph Lee was cast as Hideo in December 2024.[45]

References

[edit]- ^ a b McCaffery 1991

- ^ Walker, Doug (September 14, 2006). "Doug Walker Interviews William Gibson" (PDF). Douglas Walker website. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f McCaffery, Larry. "An Interview with William Gibson". Retrieved November 5, 2007., reprinted in McCaffery 1991, pp. 263–285

- ^ "VILETONE.COM". www.viletone.com.

- ^ Gibson, William (September 4, 2003). "Neuromancer: The Timeline". Archived from the original on December 30, 2006. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ^ Gibson, William (January 17, 2003). "Oh Well, While I'm Here: Bladerunner". Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ^ Gibson, William (January 1, 2003). "(untitled weblog post)". Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ^ Gibson, William. Neuromancer. ACE, July 1984. p. 243-244.

- ^ Person, Lawrence (Winter–Spring 1998). "Notes Toward a Postcyberpunk Manifesto". Nova Express. 4 (4). Retrieved November 6, 2007.

- ^ Mark Neale (director), William Gibson (subject) (2000). No Maps for These Territories (Documentary). Docurama.

- ^ van Bakel, Rogier (June 1995). "Remembering Johnny". Wired. Vol. 3, no. 6. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ a b Cheng, Alastair. "77. Neuromancer (1984)". The LRC 100: Canada's Most Important Books. Literary Review of Canada. Archived from the original on October 29, 2007. Retrieved September 9, 2007.

- ^ Walker, Martin (September 3, 1996). "Blade Runner on electro-steroids". Mail & Guardian Online. M&G Media. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ^ "1984 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ Grossman, Lev; Richard Lacayo (October 16, 2005). "Neuromancer (1984)". TIME Magazine All-Time 100 Novels. Time. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ Langford, Dave (November 1984). "Critical Mass". White Dwarf (59). Games Workshop: 12.

- ^ Langford, Dave (August 1986). "Critical Mass". White Dwarf (80). Games Workshop: 9.

- ^ "Books to Look For", F&SF, April 2005, p.28

- ^ Elhefnawy, Nader (August 12, 2007). "'Burning Chrome' by William Gibson". Tangent Short Fiction Review. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ^ Gibson, p. 69

- ^ Leiren-Young, Mark (January 6, 2012). "Is William Gibson's 'Neuromancer' the Future of Movies?". The Tyee. Retrieved January 16, 2012. "One of the obstacles in the selling of this movie to the industry at large is that everyone says, 'Oh, well, The Matrix did it already.' Because The Matrix—the very word 'matrix'—is taken from Neuromancer, they stole that word, I can't use it in our movie."

- ^ Gibson, William (January 28, 2003). "The Matrix: Fair Cop". williamgibsonblog.blogspot.com. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ Fitting, Peter (July 1991). "The Lessons of Cyberpunk". In Penley, C.; Ross, A. (eds.). Technoculture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 295–315. ISBN 0-8166-1930-1. OCLC 22859126.

[Gibson's work] has attracted an audience from outside, people who read it as a poetic evocation of life in the late eighties rather than as science fiction.

- ^ Adams, Tim; Emily Stokes; James Flint (August 12, 2007). "Space to think". Books by genre. London. Retrieved October 26, 2007.

- ^ de Haven, Tom; Jensen, Bruce (August 1989). Neuromancer. Marvel Enterprises. ISBN 0-87135-574-4.

- ^ Jensen, Bruce (November 1, 1989). Neuromancer. Berkley Trade. ISBN 0-425-12016-3.

- ^ "Neuromancer graphic novel". Antonraubenweiss.com. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

- ^ Buwalda, Minne (May 27, 2002). "Voyager". Mediamatic.net. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ^ "Neuromancer : Hall Of Light - The database of Amiga games". hol.abime.net. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ Kaplan, Ian Lawrence. "William Gibson Reads Neuromancer". Bearcave.com. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ "Club Foot Orchestra". telecircus.com.

- ^ "Index Magazine". www.indexmagazine.com.

- ^ "Chris Cunningham—Features". directorfile.com. Archived from the original on June 18, 2007. Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- ^ "Neuromancer Coming to the Big Screen". comingsoon.net. Archived from the original on August 9, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2007.

- ^ Gingold, Michael. "Natali takes "NEUROMANCER" for the big screen". Fangoria.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2010. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ "Seven Arts Announces New Distribution Venture With GFM Films". Benzinga. March 31, 2011.

- ^ "Will Liam Neeson and Mark Wahlberg be plugging into Neuromancer?". The Guardian. August 2, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ^ "Exclusive Interview: Vincenzo Natali on Haunter". craveonline.com. August 2, 2012. Archived from the original on April 23, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ^ "Chinese outfit boards sci-fi 'Neuromancer'". Screen Daily. May 15, 2015. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ^ Couch, Aaron. "'Deadpool' Director Tim Miller to Adapt 'Neuromancer' for Fox". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- ^ "Neuromancer: Miles Teller Eyed for New Apple+ Sci-Fi Series: Exclusive - the Illuminerdi". November 29, 2022.

- ^ Cordero, Rosy (February 28, 2024). "Apple Greenlights New Sci-Fi Drama Series 'Neuromancer' Based On William Gibson Novel". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Otterman, Joe (April 23, 2024). "Callum Turner to Star in 'Neuromancer' Series at Apple TV+". Variety. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (June 28, 2024). "Neuromancer: Briana Middleton Joins Callum Turner In Apple TV+ Series". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Cordero, Rosy (December 19, 2024). "'Beef's Joseph Lee Joins Leading Cast Of Apple TV+ Drama 'Neuromancer'". Deadline. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

Sources

[edit]- McCaffery, Larry (1991). Storming the Reality Studio: A Casebook of Cyberpunk and Postmodern Science Fiction. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-1168-3. OCLC 23384573.

External links

[edit]- Neuromancer title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Neuromancer at the William Gibson Aleph, featuring cover art and adaptations

- Neuromancer at Worlds Without End

- Neuromancer at Goodreads

- Study Guide for William Gibson: Neuromancer (1984) by Paul Brians of Washington State University

- Neuromancer, reviewed by Ted Gioia (Conceptual Fiction)

- 1984 American novels

- 1984 debut novels

- 1984 science fiction novels

- Ace Books books

- American science fiction novels

- Fiction about augmented reality

- Fiction about brain–computer interface

- Cold War fiction

- Fiction about corporate warfare

- Cyberpunk novels

- Debut science fiction novels

- Fiction about consciousness transfer

- Fiction set in the 21st century

- Hugo Award for Best Novel–winning works

- Fiction about malware

- Megacities in fiction

- Nebula Award for Best Novel–winning works

- Neo-noir novels

- Novels about artificial intelligence

- Novels about the Internet

- Novels about virtual reality

- Novels adapted into comics

- American novels adapted into operas

- Novels adapted into radio programs

- Novels adapted into video games

- Novels by William Gibson

- Novels set during World War III

- Novels set in Finland

- Novels set in Japan

- Novels set in Istanbul

- Novels set in the Soviet Union

- Philip K. Dick Award–winning works

- Postmodern novels

- Speculative crime and thriller fiction

- Sprawl trilogy

- Texts related to the history of the Internet

- Fiction about virtual reality

- Works about computer hacking